My earliest writing influences

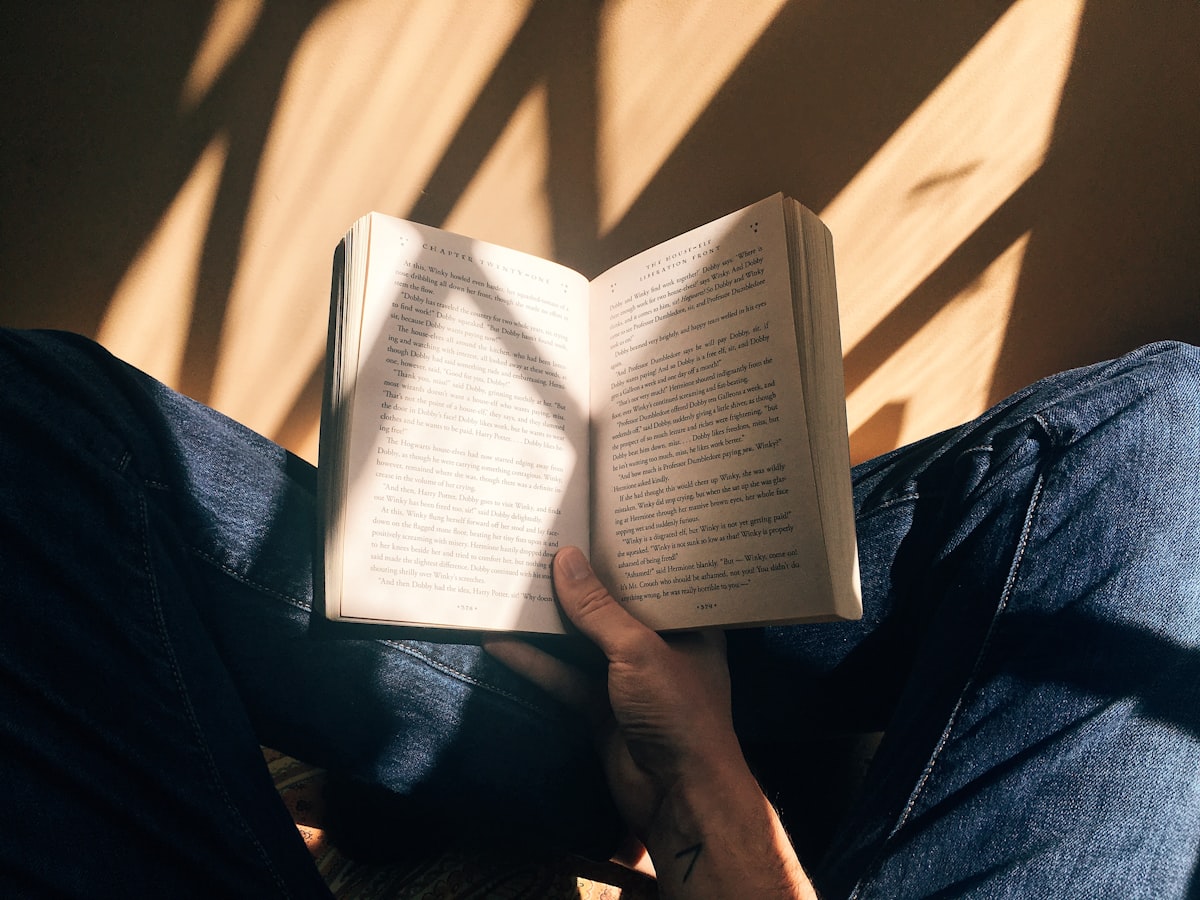

I indulge in a little nostalgia and reveal my earliest writing influences.

I'm occasionally asked in everyday life or social media who my influences are as a writer. In conversation people make some assumptions, especially when I say I write fantasy. The usual guess people make is J.R.R. Tolkien, and increasingly G.R.R. Martin — author of the highly successful A Song of Ice and Fire (and its TV spin off, Game of Thrones).

In reality, I count neither authors as a source of inspiration nor even influence. I didn't read the Lord of the Rings until I was a teenager and had already discovered and embraced fantasy as my favourite genre. As for A Song of Ice and Fire, I read the first book in my first year at university and while I enjoyed it, I became disenfranchised with the subsequent books and stopped after the third in the series. Incidentally, I stopped watching the TV show after season 3 too.

However, I grew up as an avid reader and wouldn't be the writer I am today were it not for the works of authors I discovered at key formative stages of my life.

Childhood

My relationship with books began early in life, encouraged by my mother. I become a prolific reader, devouring two or three books a week. Although I don't write for children, it was my childhood that established my love of adventure stories and introduced me to fantasy.

Enid Blyton

My mother has an outstanding collection of Enid Blyton's most popular stories. My parents hauled them all the way to Australia from my native Wales when we migrated in the mid-1980s. I devoured the Famous Five, the Five Find Outers and Dog and the Adventure Series.

By no means literature, Blyton's work was formulaic, elitist, sexist and border-line racist. Yet, in them was the importance of friendship, honesty, and the thrill of adventure that carried me back to a homeland I so desperately missed.

For the past two years, I've been reading them to my boys -- thankfully they're updated version which has altered some of the more offensive racist terms, but to my modern eyes they are still tremendously chauvinistic and elitist. Yet, as I read them to my boys I see in his eyes the same thrill and happiness that I experienced when I first read them more than 30 years ago.

C.S. Lewis

I read Tolkien's The Hobbit as a child, but I much preferred C.S. Lewis' Chronicles of Narnia. Lewis was a much better children's writer than Tolkien. The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was the first fantasy novel I read, and it's stuck with me ever since. Written of a time when children were evacuated from World War 2 London, I was enthralled by the idea of a magical world accessed through the Wardrobe.

John Masefield

Another favourite of mine was The Box of Delights, about a boy who is given a magic box by an old tinker. It allows him to change his size or travel to an alternative world. Filled with folklore from Britain's pagan and medieval past, it's part of a long tradition of British fantasy stories where the real and other world collide. If that sounds familiar, it should, as it’s the formula for The Magic Bedknob (Disney turned this into Bedknobs and Broomsticks), The Chronicles of Narnia, which I've already mentioned and of course, Harry Potter.

Teenage years

It was my teenage years when my tastes and experiences broadened. From the stalwart British writers of my childhood, I found exciting and moving works by American and Australian authors. It was also the time I began to write fantasy.

Inevitably I grew out of Enid Blyton but struggled to fill the void. Today's YA market is hotly contested across genres but in the early 90s choices were slim, particularly in books for boys seeking tales of adventure.

Australian teachers nudged school kids into the arms of authors Tim Winton and Colin Thiele, two outstanding figures of Australian literature. Yet, I craved escapism and adventure, at least in my earliest years in high school.

R.A. Salvatore

When I was 13, I made a chance discovery in my school's library.

The book I found was called Homeland, a story about a dark elf struggling to find his place in, and ultimately reject, the violent society of his race. At the time, I had no idea what a dark elf was, nor had I any idea what Dungeons and Dragons was.

Quite honestly I was enthralled from the first page. Salvatore's an excellent story-teller — certainly the best in the Forgotten Realms stable. I was pleased to discover, he was prolific too. I read my way through the remaining books of The Dark Elf Trilogy, the Icewind Dale Trilogy and beyond until I caught up to him.

Eventually, I grew out of his books. As much as I loved the character of Drizzt do'Urden, Salvatore's later works have become an excellent exercise in flogging dead horses. Saying that, he keeps his fans happy.

Jean Auel

This may seem like an odd duck in my list, until perhaps you consider my childhood career aspirations lay in archaeology, not writing. Though the later books in the series are almost a parody of themselves, The Clan of the Cave Bear is an outstanding novel. It's a tragic tale of a young Cro-Magnon girl who loses her parents and is raised by a clan of neanderthals.

Auel's description is exquisite, her research impeccable. It's world-building on par with any master fantasist. Yet, it's her characters that have stuck with me all these years. It was the first book I ever read with a strong female protagonist, and it explored subjects I'd never read before -- like loss, grief, and sexual violence.

Auel is not without critics. In an interview she once noted in her home country, her graphic depictions of Ayla's sex life earned her the rebukes of her prudish countrymen. She was also severely criticised by archaeologists -- including several under whom I studied as an undergraduate. I've read novels by archaeologists, for example Christian Jacq's Ramses Series and People of the Wolf by husband-and-wife team W. Michael Gear and Katherine O'Neal Gear. Compared to The Clan of the Cave Bear they are terrible — being an academic expert is no guarantee you can write a compelling story with compelling characters.

The Clan of the Cave Bear was the book that made me grow up as a reader and while I still loved adventure and escapism, I now wanted stories about people — their struggles, their achievements, their loves, and their losses.

Marion Zimmer Bradley

Another recommendation from my mother, was Bradley's seminal work, The Mists of Avalon. I've read many Arthurian books before and since, but this is far and away the best. It tells the story from the perspective of the women in Arthur's life, and does a terrific job in reshaping Morgaine le Fay from that of an evil seductress, to a complex character caught up in the politics of Camelot and the inevitable transformation of Britain from a pagan to a Christian land.

James Clavell

Growing up, I was fascinated by Japanese history and martial arts. My parents had a copy of a couple of James Clavell books, but it was Shogun that drew my interest. A doorstopper, I was hooked from the first page. Clavel's vivid recreation of early 17th century Japan seen through the eyes of Englishman John Blackthorn is a masterpiece of historical fiction. Impeccably well researched, Clavell blends detail with exciting narrative well-developed characters.

Raymond E. Feist

I've saved the most influential for last. When I was 15, my mother waved the fantasy supplement of the Doubleday book club catalogue under my nose and asked if wanted either one of a bundle that was on sale. The choice was between David Eddings and Raymond E. Feist. As I recall, the Eddings bundle contained more books, but something drew me to Feist.

They stayed on my shelf, saved for my first family holiday to Queensland to escape a cold Melbourne winter. I read Magician and my life hasn't been the same since.

As a writer, Feist was incubated in the 1970s American roleplaying world, with much of his world created as a Homebrew D&D setting by his mates. Yet, there’s a quality to his work that goes far beyond what I read in Salvatore’s RPG Lit. Feist reads like epic historical fiction, albeit with magic. There’s great characterisation, politics, pace, and action. Where Salvatore wrote exciting sword fights, Feist’s ability to write battle scenes without them becoming a confusing mess is without peer.

While it’s true that his later work isn’t as good, his style, craft, and handle of characters and plot has been my single biggest influence as a writer, particularly when I started writing fantasy.

Concluding thoughts

Well, that was a bit of nostalgia I enjoyed more than I care to admit. Thinking about one’s influences means you have to do a lot of self-reflection. Of course, I don’t write like any of these writers any more. I read more widely these days, and I’ve not touched on the academic writers who shaped me writing through my university years.

I don’t read as much as I used to, and in truth I miss it. Maybe it’s time I started to dust off a few of my old favourites and reconnect with my past, as well as the stories that inspired me so long ago.